The cabinets in the kitchen were lashed shut with tiny belts, which was the last straw. This whole operation was intentional, the place was buttoned up, battened down, ready to rock, sway, vibrate, bow, dance, swell, jitter and shake—all ways to come apart, lest it be self-consciously held together, which it apparently be. The door frame between the kitchen and the hallway to the staircase was reinforced, steel L-braces driven through the molding. I walked through the kitchen, equal parts frustrated and relieved, feeling like my ardor was wasted here; the house, and all of its feckless inhabitants, could take care of themselves. I ran my hand along the bannister, it too was of a heavy material, didn’t give at my grasp, and I shook it harder than any sound could, releasing it in disgust. It was I who was now feeling destructive. I wanted to see this place blasted to its cinders, reduced to empty rafters and apparently indestructible framing, where the melody couldn’t hide behind shabbily papered walls or weathered floorboards. I wanted it out in the open, apparent, unabashed, even if the power of it bowled me over. I thought it would be beautiful, and I hadn’t been forced to my knees, not yet, not quite. I gripped one of the bannister supports in my hand and placed the other flat against the wall, a conductor for the latent hum, oscillating so quickly that it felt more like fuzz, made my temples vibrate and my face buzz until my nose itched so ferociously that I had to relent and rub the irritation away. The fuzz continued to resonate in the back of my skull as I turned the corner. I sighed in relief as I approached Jack, sitting on the startlingly well-manicured, mustard-yellow divan. I hadn’t noticed before, and did now only because of how high his pants were hiked up in his sunken comportment on the couch, that he wore one red and one black stocking in place of his usual, loudly patterned men’s dress socks. He gestured to the puce chair to his left, but I needed another moment to drink in the room which had seemed the promised land when I was paralyzed fifty feet from it, out on the curb. I squinted through the window, which indeed rippled and roiled with each syncopated smack from the house, a giant cupped hand in an upstairs bedroom clapping against the floor, changing its concavity to alter the pitch. I thought I could see myself sitting beneath the tree, but it might just have as easily been Cashman, or Feli, or the person who waved to me at the threshold. In fact, it must have been the last of these, as I did not know this person, and I did not want to know them, they were unfamiliar, and mocked me with their moving through this scene of dread and curiosity. I wanted them to disappear, and so I stopped staring out the rippling glass, turned around once to note the bent nails fastening the framed art and small taxidermy to the wall, dust shaking to the floor but ornaments remaining stubbornly attached. It was time for Jack to speak, so I sat, and thus spake Jack:

“You moved!”

This time it would be I who would hold mum. I didn’t have anything to say to him at the moment, and the artificiality of my fear and sadness continued to creep up within me. I felt, plainly, that he had orchestrated all this madness, and it was pointless, and that meant that my intuitions and emotions were pointless as well. That these were patent facts did not make his suggesting them to me, especially in such a convoluted manner, any less unpleasant. Fuck him.

“So we made it through the worst of it, Mister Hammé. Everything goes in cycles, doesn’t it?”

I could not keep my resolution. These kinds of platitudes would not suffice. I needed him to understand that. But he had that playful jouissance alight in his eyes, and I decided to grip the arms of the chair and let this encounter go where it would. It was still daylight, but I was thirsty.

“Surely not everything. You’re no Buddhist.”

He slapped his thigh in laughter. “Indeed not. But here we are anyway. Did you really think I would run into a collapse? Had I wanted to die, I would have long ago. There have been so many better opportunities.”

“I don’t doubt it. I hope I have saved you from unworthy deaths at least one or twice.”

“Oh, I’m certain you have.” He uncrossed his legs, pulling up the trousers even further, revealing the complicated, finely woven patterns of the stockings. “I wouldn’t remember, though.”

“Why’s that?” Why I asked questions like those, even just to keep the conversation trudging forward, is beyond me. In this instance, though, the conversation was my best opportunity to regain my sense of the world and my place in it.

“Oh, it’s nothing against you or our history together. I think I am just saving room in my memory for the real thing, rather than wasting a bunch of memories on near-deaths. If they’re worth a damn, remembering them shouldn’t be the thing. I am no facile thrill-seeker either.”

This was true. Jack’s preferred near-deaths were sudden and unanticipated. He tended not to toe any lines which held his mortality in precarity. He pressed on, for both of us:

“So here we are again.”

“I’ve never been here before. I can’t believe you have either.”

“Well, not here exactly, but in this situation.”

“An inexplicably shaking house which ejects keyboards from open windows and features bassists in dresses as roof-dressing?”

He laughed again, then halted at this last quip. “Is she up there?” He raised an eyebrow and a grave affect drew across his face as a veil, then fluttered away. He didn’t really need an answer. “Eh, she wouldn’t want me to find her right now anyway.”

I was getting tired of that narrative, and this seemed as good a time as any to relieve myself of it.

“Why, Jack, is everyone so concerned about who wants to be found, or rescued, or gotten?”

He threw his head back in false-disgust. “You know I don’t like talking business during daylight hours. It’s uncivilized. And why are we here, anyway? Weren’t you the one who asked me to go back inside?”

I was unsurprised by the first response, and completely taken aback by the second. I was feeling short, and I hated that feeling. “How could I ask you to go back inside when I didn’t know you had been in the first place? Tell me this at least: do you want to be gotten?”

He looked me square in the eyes, his generally languid, come-hither, bedroom eyelids sharp and raised, directed. This was where Jack signaled that he was to be clear and forward with a paucity of gesture—take advantage, said the eyelids, or at least listen well, because this is your chance. This man does not dissemble as a habit—they continued—but you must nonetheless earn the truth as he sees it. I felt myself cringing.

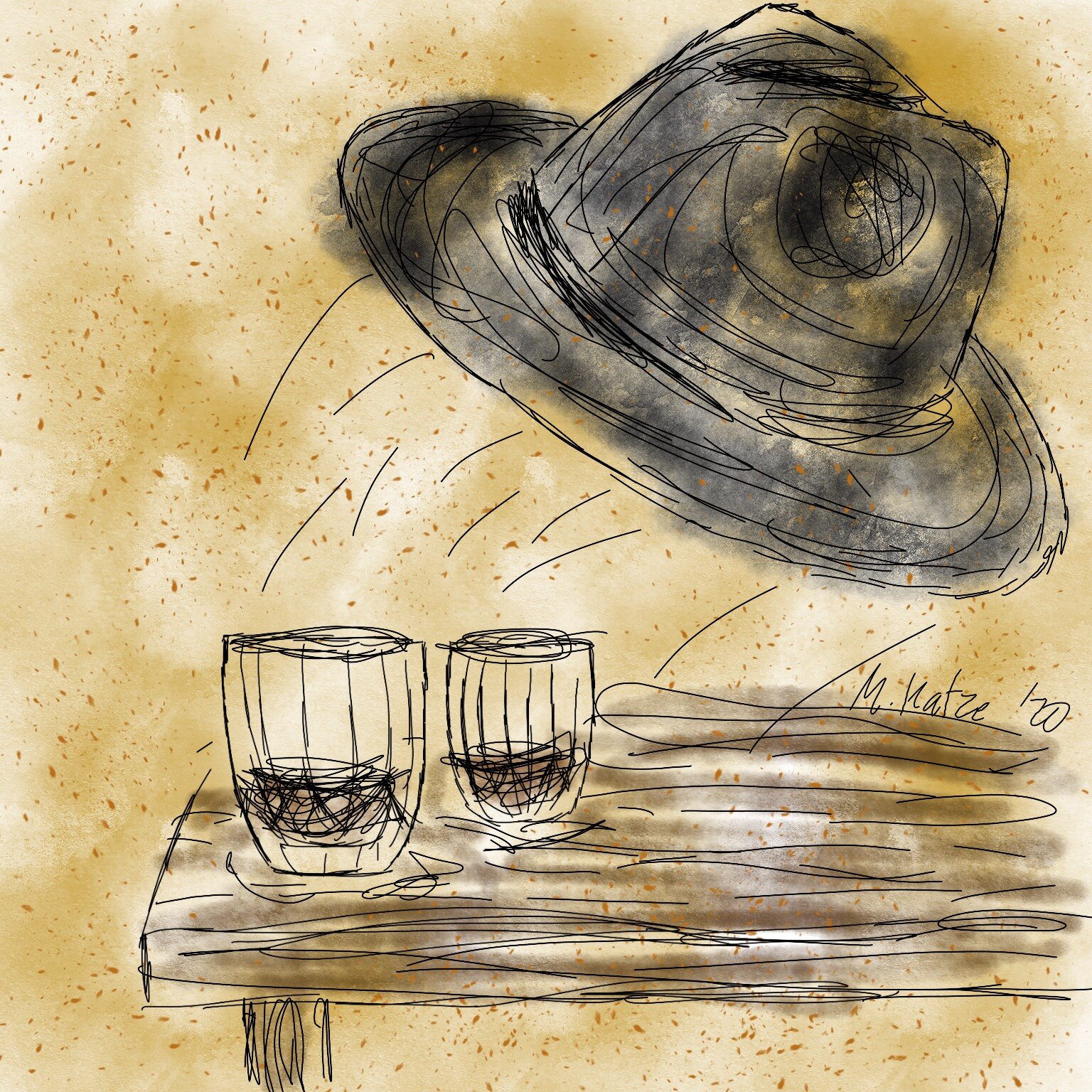

“Everyone wants to be gotten. You wanted to be gotten for years, so I got you. I am continually being gotten. But who does the getting is of the greatest consequence! The means of getting matter too! You know that, we have had that conversation before, even if not in so many words. But,” and here he moved his hat off of the end table, revealing two tumblers containing a healthy three fingers each of the only substance they could possibly contain, and handed one to me after swirling the liquid once or twice, as if to awaken it from under-hat slumber, “I can tell you want to fix something in here, don’t you? Fix it by finding meaning in it, repair it by sifting out the melody, as if there has to be a melody. It’s always about the song, isn’t it?” The giant hand clapped again, followed, as if on cue, by a whirlwind of notes, sounding like the top octave of a farfisa, arpeggiating wildly, changing one tone each time down the chord, an algorithmic shapeshifter, that seemed somehow to issue down from higher in the floorplan. I had assumed all the sound was coming from the center of the house, but as I considered it now, there was nothing to really back that assumption, based on what I had seen from outside, or underneath, for that matter. This was the first, vague sense of anything being localized at all. Jack did not look away from me as he took a sip from his tumbler.

“The song, the song!” He swept the drink around with a grand gesture before replacing it on the table. The house, or some observant party within it, knew we were together and distorted stabs that could have been electric guitar began punching against the walls and floors, and Jack’s heavy glass danced between the claps and stabs on the tiny end table. I leaned over from my seat to verify: indeed, bolted fast into the floor with rusty ties through thick, fresh black leather over each of the table’s three hooked feet. Jack leaned forward on his knees:

“You know, I tend not to like much of the new culture.” I leaned back in response to his incursion, and braced myself for whatever might sally forth. The pitches, while powerful, were low and sporadic enough to avoid shouting, so long as one punctuated their words with meaningful pauses, to avoid having to repeat themselves. “There’s just not much space for me in it, save for what I do. But what I do exists within a certain paradigm, too. I’ve never been one of those people who thought he needed to change just for the sake of change. I like to think I am forward-thinking enough to have found my spot, and now I can exploit it. I can mine it for everything it’s worth! Quite a racket up there, eh? They’re really doing some amazing work in here, testing all of their preparations, I guess.” He smiled, nodded his head a bit, as if he was finished, then realized he wasn’t finished, raised the eyelids anew, as they had slipped slightly during the last salvo.

“Anyway, nothing’s wrong. What would you change, anyway? There’s nothing to be done, because there is no problem, and even if there was, it wouldn’t be our problem! It’s not our responsibility, and nothing is broken. What else do you need to know? Think of it like a party, and try to enjoy yourself. There’s nothing wrong with trying to enjoy yourself. Maybe that is your solution to your nonexistent problem: try to enjoy yourself.” Perhaps it was the top part of his eyes, the generally hidden crescent moons, which perceived that I was not especially taken with this line of thinking, or perhaps he was just getting bored.

“You still think it is about the song!” I did not think that; I didn’t know what that meant. He was speaking as if we had discussed “the song” and I wouldn’t let it be.

“That’s fine, you can think that,” which I didn’t, “but you don’t need to knock around in here alone. I am fine, if you were concerned,” which I wasn’t, so much, at least not anymore. “Dallow is around somewhere, so there’s that. I think I’ll wait down here and see if she comes down. You’re certain she’s up there? So strange, so very strange.” He shook his head and leaned back, now certain that he’d finished. “Very, very strange.” Another clap, this one enough to send his tumbler to the floor, where it did not shatter, though emitted a high-pitched tinkling crack. Jack scooped it up, drained the last drops, and set it back on the edge of the table, perhaps a third of its base off the edge, and grinned his devious grin at me, raising one hand in the air like a minister or a rock star, not that he had to choose, awaited the next clap-and-stab combination, heard the smash on the floor and slowly dropped his hand back to his side, satisfied. Now he had to be done. He almost whispered, forming the words with his thin lips deliberately, so I could make them out in pantomime: “So, so strange. So strange.”

I stood up, took one last, long look at the rippling waters of the picture window, and turned to leave the room, hopefully forever. I had evacuated the foreboding magic of the place, sat across from my cohort and learned nothing new that made any sense to me. I did not dread, but I was again alone, and that was the salient effect of this place, from within or without: it made me alone. Something dropped above me, the unmistakable thump of your upstairs neighbors moving furniture indelicately, for whatever reason, tipping over an old television, or refrigerator, or bookcase—the sound of rectangular heft. Standing at another threshold, this one to the hallway and staircase, I heard human voices, live-sounding human voices, sharp, accusatory tones blended with acquiescent, calming ones, filling out the inhaling vacuity between stabs. Then, finally, one more clap that reverberated with mellifluous echoes, and I fought every instinct to turn around and touch the glass picture window, perhaps press it out and take Jack by the hand, away from this place. Instead, the waves of echo dissipated into the void, wherever sound goes when it is done sounding, in this case, into the walls and through the floor, back to whatever capacitor waiting to discharge, whatever reservoir to overflow, and the choir blasted through, pure and unmistakable, but overdriven and possessed of a fury somewhere beyond divine.

The feet which stumbled, as if turning around after taking the first stair and then being carried by momentum down the next couple, the first few steps in my line of sight had to be Dallow’s, well-worn though still taut, ostensibly black though really charcoal, if we’re being honest, denim tucked into two-toned brown spectators, all dappled, all weathered dapper. He might have been listening to the power of the choir’s second great chord, and then, as it dropped into ululating, staccato bursts, still too overdriven to discern any linguistic pattern, at least for me, continued his rather labored descent. He saw me, wholly unsurprised, and leaned over the reinforced bannister.

“Pretty good, eh?”