The attic is hot, as attics are, but I quickly dismiss my wondering how anyone could spend any time up there. The wood is newer, and the oaken smell is pleasant, mingling with the open windows which add the scent of the green tops of trees adjacent. But it is also a sonic funhouse, removable baffles stuck between each two-by-four running from baseboard up to meet at the point of the A-frame, floor unfinished hardwood with two open gaps, one for the ladder stairs up, the other for the echo chamber down. The boys are working the furnace down there with renewed vigor, and I remain a barely corporeal entity, observing outside myself, marveling at the instincts of these appendages of mine which balance and wince at each next cascade and wallop of sound. They have found some kind of psychic wavelength, and the tones are ordering themselves in recognizable patterns. I wonder if this is repair.

What it certainly is is motivating, rocking me back and forth, suggesting I return to thoughts of ruin and renewal, and would I be more satisfied at the roof collapsing in from above or the floor giving way below. Repair implied a few things, none of which totally fit the situation in which I found myself, about which I begged my compatriot to tell me truth, as a result of which I rocked in this attic. The waves of melody spun into glissando, but still perceptibly back and forth, the top of a skyscraper swaying in deceptively high winds, but this was no skyscraper, and the air outside was dead still. Repair meant that something was in disrepair, a quality which described my own intuitions, but which was defied by the caterwauling, furious sound driven through the old house, and the old house’s persistence, resistance, acquiescence, quiescence in the face of it. Repair, to me, at least, also meant that there was some prospect of restoration, but then, what required restoration, anyway? There was a hand to place on my shoulder, and a shoulder for my hand, the entire circuitry was intact, if altered. I closed my eyes and rocked, trying not to try not to concentrate on my balance, as tumbling over might break through the floor and send me into a room to which I sought access, but was never granted it.

I had, nonetheless, come up here to see about Moist, and so the tides of sound carried me over to where she sat, opposite the echo chamber. She spoke, then looked up at me:

“What do you think he wants?”

I did not know what he wanted, any more than I knew who he was, but her look, straight into my eyes, clear and motivated by nothing save expecting I might have an answer. I had a few paths I could take here, and I briefly thought of each as I continued to strafe each next wave of melody. I could make something up, or lie outright, violate the credulity of the question and asker under the auspices of providing relief or simply being accommodating. I could ask my own quite glaring questions under the reciprocal assumption that she would know things I genuinely wanted or needed to understand, about music, the smell of wood and foliage, and how this would all end. Or I could throw it in another direction altogether, to comfort someone who may not need comforting with conversation unmoored from the alienation of our shared surroundings. But she relieved me, reading my mind, and stood, placing her hands on my hips for a moment as if I were a ballet dancer, or, better, as if she were planting me in the ground.

“How do you think it will end?” She asked, this time with a slightly more pleading tone, knowing I held the answers, understanding only slightly why I would withhold them from her. I had fewer choices at this second entreaty. She dropped her hands from my sides to her own.

“I wanted it all to fall down,” I somewhat blurted, speaking quickly for fear of losing this fine gossamer thread between myself and this person. “I went from hoping it would stand long enough to save my friend to hoping this entire place would collapse around me. They are working hard downstairs to see my hope through, but it may be too well-built for all that.” The engine room responded with a distorted burst of brass fanfare which oscillated and faded into the symphonic movement which continued to develop. Moist looked skeptical, as if I had not finished my thought. I tried to think of more, but she persisted.

“And where is Jack?”

“He is in the living room, having a drink.”

“Why didn’t he come up here?”

“Because he isn’t worried about anything.” This, I was certain, was true.

“What will it take to bring it down?”

I didn’t think she wanted to know that. “I don’t think you want to know that, or what I think about that. It’s all I have been thinking about, for hours. It’s clear that everything has been tried, without actually taking axes to the walls and sledgehammers to the foundation. Maybe that feels like cheating. It’s supposed to just fall down of its own accord, as if it’s given up. It’s such a powerful sound—”

“Don’t you think it’s beautiful?”

“I don’t know.” Which was a strange thing to say, because I think I did think it was beautiful. But it gnawed at me still, even as I found my place in it. I couldn’t imagine operating the tools the two below us did, and especially not in the way they did. A buzzing in the background, the ambient canvas they affixed to the walls behind the images which otherwise hung in the air, hit a frequency which made my back ache and my left shoulder tense up. Moist saw me wince, but waited for me to go on. I wanted to tell her about lying down.

“I think I almost escaped, or I almost understood, which might be the same thing. I lay down—”

“On the floor?”

“Yes, on the dirty floor. But it was not so dirty on the rug, and just soft enough to cradle my tired spine.” It really did smell lovely up there, as if the peaks of sound depressed the aspirator of oaken wood and leaf. “I stopped searching and relented, letting whatever would happen, happen.” I reflected on the experience with the musicians for a moment, realizing it was the most people I had been around all day, though still with only one to whom I could speak. There were three of us now, and Dallow was busy peering dangerously down the echo chamber, squinting as if to make something out below. I considered whether I had wanted to relent.

“Were you trying to let go?”

“I guess so. I didn’t know what I was letting go of. No one had forced me to come here, I had done so out of some kind of duty. But I was gotten.” This was an incredibly clumsy phrase. I did not know how to put words to the experience, and I had not tried to yet, perhaps as a result of not knowing how. I did not want her to ask who had gotten me, or why, and she did not.

“How were you gotten?”

I remembered, combined memory then with impression now, tried to find the image hanging in the air, when I was briefly the canvas. Though what would have to happen began to dawn on me as I spoke. “I succumbed to this place for a time. I lay back and it lifted me, the sound in the air, and the music that we are hearing and feeling.” I was doing a poor job of it. “Listen, I let it all go. Nothing mattered, and I saw all the color in the place beneath the dust and the fading from the sun and the years. There was never meant to be a roof, and maybe not walls or a floor either. This was all built long ago, for some other purpose. And that purpose was never realized, or if it was, there is no record of it. No one here recalls how it became…whatever it is now. A giant speaker. A megaphone for impossible ideas. It’s a living organism that cannot figure out how to die. And we are blood in it now, and it will not use us up, whether we give over or not. It will let us add to it, but never take away. So when I lay down on that floor, I might have thought I would understand, but not even Furey and Poor Old Jeffrey Young understand what they are doing. Maybe Feli did, but he knew to walk away. Maybe Cashman did, but he had somewhere else to be. Maybe Dallow does, but he is staring down the hole in the place, all the way to the bottom. It’s hot down there and it’s hot up here, but at least here I can smell and that means I am alive.”

“Should we try it?” Of course she was right.

“I got through the ceiling once, I suppose, because now I am up here with you. And you got through this roof once yourself, when I saw you, up there alone.”

She looked up at me and then down at her hands. I heard, or rather more felt, the next crescendo rolling up from below, a rumble that felt more like the effect of sound being produced than the intentional music toward which the gentlemen were now gesturing. Then an andante sequence of three notes, middle—high—low, repeated four times, far too loud for even what had preceded them all this time, before they were choked off, as if one of the two men had slipped and turned a dial too far or pushed a fader too high. But that seemed so unlikely to me, that anything was random or accidental felt impossible, and I did not want to believe it was so. Dallow steadied himself and stood upright, looking over at us from across the attic with eyebrows raised and lowered, impressed at the musical persistence. Moist and I both returned his smile before an incredible bass note blasted out like a foghorn, sending Dallow to the floor, still grinning, and there was naught to do but grin. Moist and I laid down a few feet apart, as if to rob the sound of the satisfaction of knocking us over, but I knew what was to come. The three note pattern struck up again, it was too much, it did not hurt my ears so much as made me fearful of what the place might still be capable of. I lolled my head onto the right cheek and saw the word “Bernoulli” burned into the floorboard next to me, and it smelled fresh, a further counterpoint to the perfumes of the attic, though the resonance of the three notes rattled my skull and menaced my brainstem, and I righted myself quickly. The pattern continued, and I could not believe we had not yet been lifted, save for the fact that I felt sucked toward the floors below, and maybe it would be crashing through rather than being caved upon that would end it. Then, finally, the grand exhale for which we had all been waiting, I heard the crack, but this one was real, could not have been produced electronically. It was lightning that splits the sky in spidery patterns before the storm follows, a warning which you do not heed and are instead caught atop the hillside overlooking the lake, knowing full well that you are soon to be soaked to the bone, bone-deep, and either happy that it will compromise your thin clothing and bring you a few millimeters closer in embrace to the one with whom you’ll soon be soaked, or else profoundly struck by your aloneness in a world that would place you on higher ground in the deluge alone. It was the scream of the hillside river birch which has given way seemingly of its own accord, no natural force testing its strengths, a splitting for reasons unknown and not to be known, cosmic randomness on a personal scale, audible from that same hillside in autumn or the rocky beachhead below, sudden, startling, then past. But no, it wasn’t either of these, really, as it continued on too long and was trailed by a moaning report too deep. It was, instead and again, a feeling as much as a sound. It was the lake ice, uncertain and hidden beneath light snowfall, splitting and splintering, your weight having offended its callow state, and it was to give beneath your feet. You began to run as if it could be outrun, you pretended it was visibly scoring between your running legs, icy twinkles accruing to one great shattering to come, and the collapse followed behind you, a glacial triangle upended and drawn into the floes beneath, and you, clinging to the reeds and chest-deep in near-frozen water, you cracked your own face into an icy, satisfied smile at your power to return solid to its liquid state and live, if only just, to tell the tale.

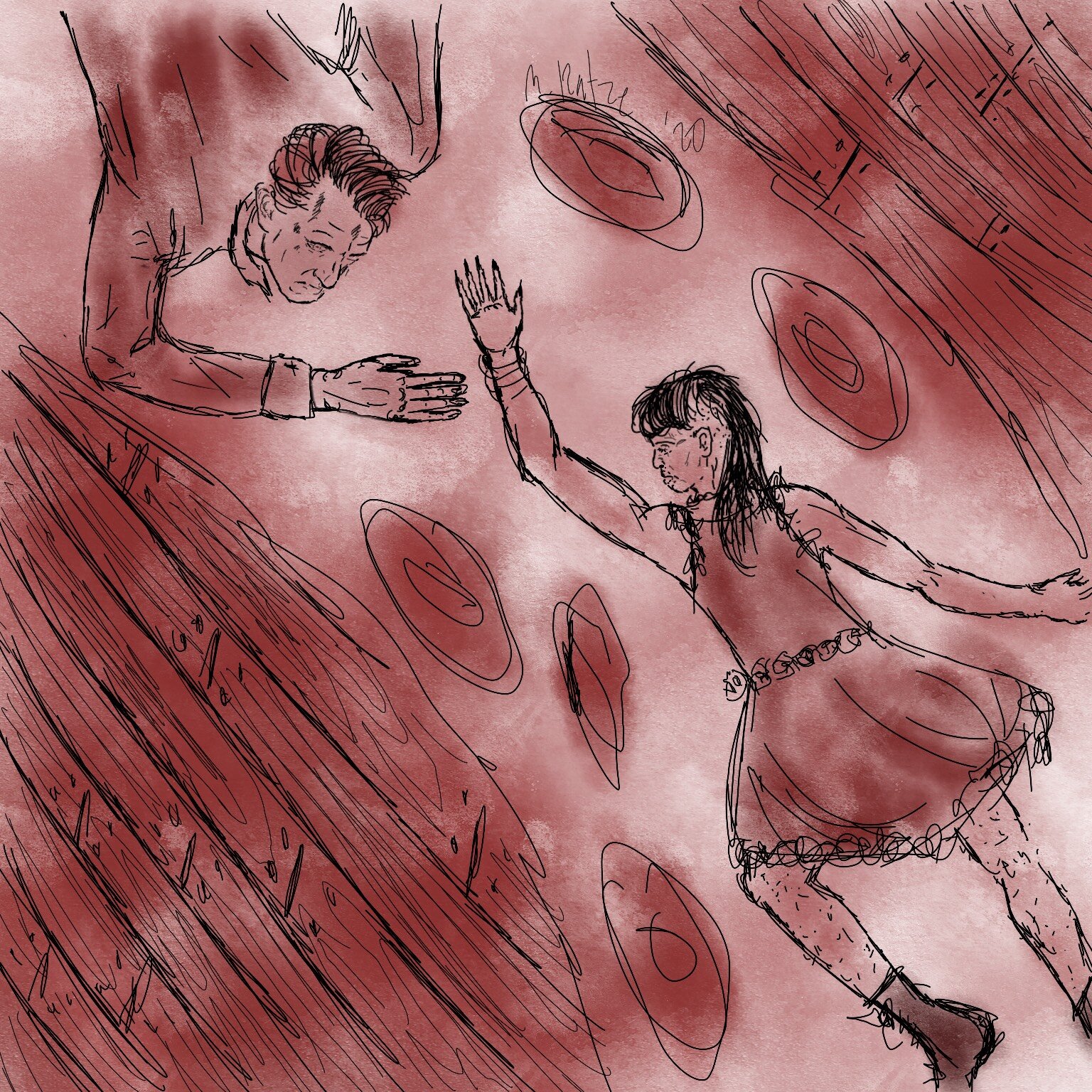

But we do not see the lake ice being pulled under by avaricious seaweed and sleeping fishes. Moist and I see a man and his hat, generally inseparable but now detached, crumpled against the far wall, a 6/8 tarantella berating him angrily, periscopically from the shaft beside. The 8 is eighth notes pulling a foreign scale downward, the 6 a jaunty, inappropriate dance, and the punishing three-note theme is the counterpoint against which both battle. The choir has gone home, there’s no need for it here, the richness and amplitude was entirely sufficient to bring our man down. Moist and I look at each other with a combined sense of bemusement and duty, and know there will be no transcending above, only receding below.